I love time. I love the idea of time. I love the concepts of time. I love the history of time.

Get it? I’m fascinated by time.

I’m not talking about a Steven Hawking-level consideration of time – the metaphysical consideration of when and how time started. I’m more down to earth. Literally. My fascination with time is rooted in the practical applications of time. How it is measured, how it has effected human history, how we use it and how it affects our daily lives.

I have worked most of my life in professions and disciplines that are ruled by time. The US Army takes time very, very seriously in both the practical human dimension (“The meeting starts precisely at 1430. Be there!”) and in the absolute system dimension (example: the anti-jamming systems built into our military radios are based on extremely precise time synchronization). As a soldier you very quickly become aware of how important time is to the whole organization and you ignore it at your professional peril. Some of the biggest ass-chewings I got in the Army were for missing meetings because I lost track of time.

In the civilian world I manage systems that are ruled by time. I manage the GPS-based surveying and precise positioning systems at the worlds busiest airport. At its very core, GPS is about the extremely precise measurement of time.

I am surrounded by time, immersed in time and, occasionally, consumed by time. And it fascinates me.

It’s All About Time

Mankind has always been fascinated by time. It seems that once we realized that we needed to track things – planting seasons, birthing seasons for domestic animals, festival times, etc. then the concept of time took hold in the human psyche and has never let go. In fact, I believe that it is the understanding of the concept of time and the ability to consciously plan against future time that is a uniquely human trait and one that separates us from the lower species. The understanding and use of time is very much a part of the human ‘spark’ that philosophers talk about.

Virtually every advanced human civilization was fascinated by time. The Mayans, the Chinese, the Greeks and the Romans all expended enormous intellectual and physical capital in the development and maintenance of time systems, first in the macro application (accurate calendars) and then in the more precise daily measurement of time (what we think of today as clocks). The more complex the civilization the greater the interest in, and need for, accurate timekeeping.

Two of the great monotheistic religions, Christianity and Islam, were obsessed with time from their beginnings. Ritualized daily prayer was (and in many cases still is) a driving force in these religions, so the need to accurately divide the day into equal parts drove a cultural fascination with time and timekeeping. While the Christian concept of ritualized daily prayer has become sloppy over the past thousand years or so, Islam still holds fast to the tenant. The fascination with accurate timekeeping remains a critical part of the Islamic culture.

|

| The Al-Jazari candle clock |

(I have been told by several sources that it was the Islamic world that kept the Swiss mechanical watch industry alive in the 1970s and 80s. As the quartz watch craze swept the Western world sales of quality mechanical watches dried up in the that region. However, the demand for high end mechanical time pieces grew with Middle East customers who were flush with petro-dollars and a fascination with time. Eventually the West came to it’s senses and the mechanical watch industry is healthier than ever.)

The human need for accurate timekeeping reached a peak in the early 18th Century with the explosion of sea-borne international trade. By the late 17th Century we had accurately mapped the world, located the continents and key cities, and identified commercial markets. The sea-borne trade routes had been laid out, efficient ships developed and a whole maritime infrastructure established that was poised to exploit the exploding demand for international goods. The problem was that countries and corporations were losing too many ships to bad navigation. What was lacking was an accurate, easily understood and easily taught method of determining a ship’s longitude (location east or west of a prime meridian) while at sea. Fixing latitude (location north or south of the equator) was well understood and easy to determine with simple instruments, but developing a method to easily and quickly determine longitude from the deck of a rolling ship in the middle of the ocean was a problem that had vexed the best minds of Europe for hundreds of years.

By the early 1700s highly accurate land-based longitudinal determination had been going on for over 50 years, but it required complex astronomic observations and the use of large, heavy and fragile pendulum clocks. What was needed was a simple and accurate method that could be easily practiced by marginally educated ships captains across the maritime fleet. The best minds of the time understood that accurate timekeeping was the key to solving this problem, but clocks that could keep good time aboard a pitching and rolling ship were beyond the technology of the time, or so they thought. In one of the earliest examples of government sponsored applied research the British Parliament launched a competition to see who could develop an accurate method of determining longitude at sea. The ultimate winner of that prize was a self taught clock maker named William Harrison, who gave the world the H-4 chronometer and made accurate maritime navigation a reality.

It was all about time…

|

| William Harrison’s H-4 Chronometer, 1760 |

(I glossed over far too many of the details related to longitude determination and the development of the chronometer, so if you want the whole story I strongly recommend you read Dava Sobel’s minor classic Longitude.)

The Industrialization of Time

For the next 200 years the mechanical clock was refined, standardized, downsized and mass-produced to the point that the pocket or wrist watch, the mantle clock and the bedside alarm clock were affordable to the common working man. As industrialization pushed forward and workers flocked to the cities to meet the growing demand for labor, time entered our collective consciousness as never before. Suddenly a man had to be on time. On time for work, on time for lunch, on time to church, on time to the doctor. Industrialization made cheap time pieces possible while at the same time driving the requirement for better time management. One requirement fed the other.

|

The Big Ben mechanical alarm clock.

My Grandmother had one of these

and when it went off there was

no mistaking the message:

“Get your ass out of bed!” |

The concept of parsing a day into discreet time segments for specific functions was a revolutionary concept. For most of history the worker’s day was ruled by three time checks – sun up, noon and sun down. The roosters took care of sun up, the bell in the church steeple took care of noon and his own eyes took care of sun down. That was all that really mattered. Starting in the mid-1800s, with a watch in his pocket the common man could now easily and accurately plan his day. When the boss told him to be at work at 8:00 he could backwards plan and know that if he wanted to be at work five minutes early he needed to catch the 7:30 street car, meaning he had to be out the door and on his way to the street car stop by 7:25. Likewise, if his wife told him dinner would be served at 6:00 he knew he needed to leave to saloon by 5:45 for a brisk walk home, knowing it took at least 15 minutes for the smell of beer and cheap cigars to blow out of his clothes.

But whose time was he following? You see, all time is relative. For our prototypical common man working in the mid-1800s the answer was simple – set your clock to the boss man’s clock. In fact, even today that’s a good idea (ha, ha). But what did the boss set his to? This was easy too – just set it to local time. Most clocks were regulated to local noon. The problem is that local noon is different everywhere. This wasn’t a real big deal until the railroad came to town.

For a few decades during the mid-to-late 1800s the railroads simply make use of local time. This was when railroads were a regional phenomenon with fragmented ownership. Local time was a recognized problem, but it was manageable. However, after the Civil War and the massive railroad consolidations and the push for a transcontinental rail line the major line operators realized that using local time simply was not going to work anymore. There were too many time changes as trains flew down the tracks (at a blistering 40 mph) from one town to the next or one state to the next. Since the railroads operated on a time coordination system and single rail lines were shared by multiple trains, time management became an absolutely critical issue. After a few horrific and highly publicized train crashes in the 1860s (due mainly to poor time coordination) the railroads introduced the concept of coordinated railroad (or railway) time. It was the railroads that gave us the time zones (EST, CST, MST, etc.) we use today!

The railroads knew that for all this to work they needed to precisely synchronize time between stations. They adopted an ingenious solution that remained in use for over 100 years. Using the time signal service of the US Naval Observatory, time signals were send down the telegraph lines to allow station masters to synchronize their local station clocks. For the first time the US had a coordinated time system. For the first time someone in Denver could look at their watch and know precisely, in Denver time, when their aunt in Boston would be sitting down to dinner. It did not take long for the railroad time management standard to become the defacto national time management standard. It simply made good sense and brought order out of chaos.

The railroad industry’s demand for accurate and synchronized time spurred an interesting development in watch making – the railroad watch. Since time synchronization was absolutely essential to railroad management and safety it was imperative that all railroad line personnel (station managers, supervisors, conductors, engineers, etc.) carry time pieces that met a certain standard for accuracy and reliability. This requirement triggered the production of some of the most accurate mechanical time pieces ever developed. My Grandfather Winterberg was a maintenance supervisor on the Erie RR in Buffalo, New York during the early 1900s and carried an Illinois Bunn Special. My mother used to reminisce about watching her father wind the watch every night before going to bed and going with her mother to a jeweler in downtown Buffalo to have the watch checked and adjusted (a regular requirement imposed by the railroad). That very watch sits proudly on my mantle today, ticking away merrily almost 90 years after it left the factory.

|

The movement of a Bunn Special railroad watch.

Not mine, but very similar. The movements of these watches

are absolutely stunning examples of early 20th Century

industrial design and execution. |

The Digitization of Time

Let’s skip forward a bit. By the late 1950s America had ‘jet age fever’; the WWII generation and very early Baby Boomers were fascinated by the promises that the new electronics industry offered. The potential of the new science of electrical miniaturization seemed limitless. Computers that could fit under a desk, TV sets that used fewer vacuum tubes, pocket transistor radios that received AM and FM. Why, someone was even talking about using microwaves to cook food! Wow! In 1960 the Bulova watch company jumped into the market with the Accutron line of watches and they were an immediate hit. Here was the first consumer grade watch that was fully electronic. The Accutron made use of tuning fork technology to generate the time signal and it proved that fully electronic watches were not just technologically feasible but that they were accurate, practical and that there was more than enough pent up consumer demand to make them profitable.

The other impact of the Accutron and all similar designs was that consumer-grade electronic watches could now be made that met or surpassed the accuracy of high end mechanical chronometers. For the first time ever the low level account executive wearing his Accutron to the company Christmas party could know precisely what the time was with as much confidence as the Senior VP wearing his Rolex Oyster. Accurate and precise time keeping had been brought to the great, unwashed masses!

Workers of the world, rejoice! You can now time the start of the Jackie Gleason Show with the same precision as your bourgeois oppressors in the executive wash room!

Let’s pause for the ‘so-what’ factor here. So the low level account executive now has a relatively inexpensive watch that offers the same accuracy as the Senior VP’s high end mechanical chronometer. So what? Well, the ‘so what’ is really the understanding that inexpensive, high accuracy time keeping is about to be unleashed on the consumer in ways he or she could never predict. The Accutron watch was just the first manifestation of that trend.

Let’s also pause to consider just what we are talking about when discussing accuracy. There are several accuracy standards in the watch and clock making industry, but let’s use the most common and best understood: the Swiss COSC certification standard. The COSC standard for chronometer movements states that a mechanical movement can lose no more than 4 seconds per day or gain no more than 6 seconds per day over a 10 day test period. Keep these numbers in mind as we move forward.

The mechanical tuning fork design of the Accutron design was good, but was ripe for improvement. Nine years after the Accutron’s debut Seiko introduced the technology that would revolutionize the time keeping industry – the quartz watch. The quartz watch follows the Accutron concept in that it uses an element oscillating (vibrating) at a known frequency to regulate the time signal. In the case of the quartz watch that element is the quartz crystal. The Japanese talent for miniaturization and integration meant that the basic quartz movement quickly found it’s way into a broad variety of watches and other time keeping and time control devices. The physical size and power requirements of the quartz time movement went down and the accuracy improved. The Japanese electronics industry cleverly leveraged it’s lead and expertise in quartz watch movement technology into a multi-industry colossus and Japanese companies like Seiko and Casio continue to dominate the worldwide digital watch markets.

|

The Seiko Astron, the world’s

first quartz wristwatch |

Now let’s take a look at those COSC standards I mentioned earlier. The demand for mechanical ‘certified Swiss chronometer’ watch movements goes up year after year. The market for high end mechanical watches is virtually insatiable. Manufacturers like Rolex and Omega grind out watch movements by the thousands every year. Each movement is tested by the Swiss COSC organization and those that pass receive an official Swiss chronometer certificate. The problem is, the COSC accuracy standard in today’s terms really isn’t all that strict. Remember, to receive a certificate a mechanical movement may not gain more than 6 seconds per day, or lose more than 4 seconds per day. The average quartz watch from a reputable manufacturer easily beats the COSC mechanical chronometer standard. I have a $29 Timex quartz watch that has lost roughly 1.5 seconds over the past 10 days. That’s a 0.15 second per day loss.

[The Swiss COSC organization does have a quartz chronometer standard that is quite rigorous and any consumer-grade quartz watch would find it tough to meet the standard. We are talking accuracies in the neighborhood of a few seconds per year vs. a few seconds per month with consumer grade watches. Astounding accuracies by any measure, but right now we are discussing run-of-the-mill quartz movement accuracies vs. mechanical chronometers.]

Watch enthusiasts will scream that I’m ignoring a LOT that is related to quartz movement accuracy and stability, and they are right to criticize. However, the point here is not that a cheap quartz watch can beat a high end Omega or Rolex, but that technology brings increasingly accurate time keeping to the consumer at lower and lower prices.

Today a consumer can walk into just about any watch retailer and for less than $100 purchase a quartz watch that beats a Swiss chronometer. Now that is progress!

|

The lowly G-Shock beats the Rolex?

You bet! In accuracy, that is. |

The Sky Is (Not) The Limit

As you can tell, I think quartz watches are ‘da-bomb’; precise, rugged little time keepers that truly take a lickin’ and keep on tickin’ (props to John Cameron Swayze). But accurate time doesn’t stop with the oscillating quartz crystal. Time and technology march on and today the average consumer has newer, even more accurate time options.

I began this blog post with the discussion of how time and the concepts of time have fundamentally changed human culture and behavior. Well, current and emerging technologies are poised to have an even greater impact on how time influences our lives.

Everybody knows that atomic clocks are as good as it gets for accuracy.

The first word is GPS – Global Positioning System. (OK, three words, but who’s counting).

The second word is embedded, as in embedded (or integrated) technologies.

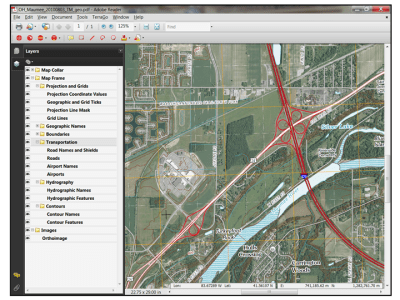

Let’s start with GPS. Everyone knows GPS is ‘those navigation satellites’. GPS is what your Garmin uses to fix your position. What most people don’t understand is that the GPS system uses the concept of time shift to calculate position. The GPS satellite broadcasts it’s position and precise time. Your GPS unit receives that signal and calculates the time shift from when the satellite sent the signal to when it was received. Knowing that the signal travels at the speed of light, your receiver can calculate where it is in relation to the satellite (just remember, you receiver needs the signals from three different satellites to fix your position).

To calculate an accurate time shift you need highly accurate and precise clocks at both ends – in the GPS satellites and in the receiver. Each GPS satellite carries three or four atomic clocks accurate to about 50 nanoseconds (that’s 0.0000000050 seconds!). But clearly we can’t stuff an atomic clock into each GPS receiver. This is one of the neat tricks of the GPS system. Since your GPS unit receives the time signal from the atomic clock in the satellite and it knows that signal is traveling at the speed of light and your unit is receiving the time signals from multiple satellites which allows it to average out error, with a cute bit of programming your GPS receiver is transformed into a ‘slave’ atomic clock. This is how every single GPS receiver works.

|

A GPS satellite. There are always 24 in orbit providing

worldwide coverage 24/7. Each satellite carries four atomic clocks. |

Accurate time tracking and synchronization is the fundamental principle behind GPS. Every GPS receiver tracks, manages and calculates time to atomic clock accuracy and precision!

Businesses and services that used to rely on expensive atomic clocks for accurate time measurement now instead use the GPS time signal. For example:

- Did you know that there is a GPS receiver on top of virtually all cell phone towers in the US? No, the tower owners don’t want to track the location of their towers in case they get stolen (ha, ha), but the owners are after that highly precise and accurate time signal. Precise time management is how cellular systems handle the transfer of a phone call from one cell tower to another. As you cruise up the interstate yakking on your cell phone your call is being automatically transfered from one cell tower to the next and the synchronization of that transfer is managed using the highly precise GPS time signal.

- Computer networks that require highly precise time synchronization use GPS receivers as their time signal source (rather than the network time protocol servers).

- Secure radio networks use the highly accurate and precise GPS time signal to manage ‘frequency hopping’ for all radios in the network, reducing interference and increasing security.

The next innovation is integration. Manufacturers are making GPS receiver ‘chips’ that are incredibly small. How small? Check this out:

|

| iPhone 3G main board |

This is the main circuit board from an iPhone 3G. Circled in yellow is the GPS receiver chip. That chip is less than 4mm x 4mm! GPS chips are now built into virtually all smartphones and are being embedded in laptop computers, PDAs, tablet computers, personal training devices and a whole host of consumer electronics that are designed for use out of doors. Unfortunately so far this integration only takes advantage of the GPS location capabilities, not time tracking and synchronization.

This brings us to close to the end of our journey through the history of consumer time. With the advent of board-level integration of GPS in consumer devices the market is poised to take the next leap in time measurement for the common man – atomic clock quality time in the hand or on the wrist!

However, two simple developments need to take place.

The first is the use of the GPS time signal to update the internal clocks of consumer grade GPS receivers. All GPS receivers have an internal clock or, for board mounted chips, receive a time signal from another timing device on the circuit board. The internal clock maintains basic system time when the receiver is powered down and, in most cases, drives the time display on the device. As silly as it sounds, most consumer grade GPS devices do not use the GPS time signal to continuously update the internal quartz clock! For dedicated GPS units the system may do a clock synchronization when it is turned on and first achieves GPS lock, but from there the quartz clock may drift out of sync. For embedded systems (like the iPhone GPS chip seen above) the device only uses the GPS time signal to calculate position. The device firmware does not allow the GPS time signal to update the system clock (a shame, because the iPhone’s internal clock is notoriously inaccurate). While most users don’t really care about atomic clock accuracy, it is a shame to not take full advantage of that exquisite atomic clock signal coming from the satellites.

Next is the integration of GPS receivers into consumer grade wrist watches. Manufacturers like Garmin and Suunto currently integrate GPS into their watches, but these are purpose built devices designed for specific functions like sports training or wilderness hiking. They are not general use watches. What watch manufacturers need to do is integrate GPS into the watch specifically for time synchronization. Make the technology invisible to the consumer – all he or she needs or wants to know is that the watch updates itself whenever it is outdoors and it’s really, really accurate! The technology is already there – Casio and others make extensive lines of watches that sync nightly with the time signal broadcasts in the US, Japan, Europe and China. While this is a neat (and useful) trick, the concept is somewhat flawed because the signals are available in only limited areas and they are easily masked or disrupted. Since these watches already contain a radio receiver and antenna system to pick up the broadcast signals; swapping a radio receiver/antenna system for a GPS receiver/antenna system should be a fairly simple feat. With GPS the synchronization signals are available worldwide 24/7.

Technology is on the cusp of putting atomic clock-quality time in the wristwatch of the common man. We are almost there. Do we need that level of accuracy or precision to guide our common daily tasks? No, of course not. Should we push to achieve it? Of course! The technology is available, proven and cheap.

So come on Casio! Get to work on it. I want my watch by Christmas!

_____________________________________________________

Thanks for hanging with me, dear reader! Before I close let me clear a few things up.

First, I’m not trashing today’s mechanical watches. From an aesthetic point of view the mechanical watch has a heart and soul that the digital watch utterly lacks. I love mechanical watches (and own my fair share). They are wonderful time pieces that continue to please.

Next, there are a number of ways to make quartz movements inherently stable and extremely accurate, but those methods only seem to be used on high end watches and chronometers because each unit needs to be individually calibrated and adjusted. It is actually easier for a manufacturer like Casio to build a watch using a consumer grade (but still quite accurate) quartz movement and off-load the synchronization task to an external service like the WWV time signal out of Fort Collins, CO. A slick and cheap trick that actually works!

And last, when I started writing this post over a day ago I wasn’t really sure where I’d go with it. I know I wandered around a bit, but my research has taken me from the history of timekeeping to the concepts of industrial time management to the development of electronic watches to the exploding field of GPS time synchronization. It has been an interesting and educational experience and I hope you’ve learned something along with me.

Thanks!

Brian