I spent my teenage years growing up in Maumee, Ohio, on the banks of the Maumee River just south of Toledo. Maumee is a lovely little town that has changed little since my family moved there in the early 1970s. The northwest Ohio region and the Maumee River played an important role in the early history of the United States. The river’s direct connection to the west end of Lake Erie made it a key transportation and trade route into what at the time was referred to as the Northwest Territories. The British had long considered the territory as Indian land and only maintained military and small trading outposts in the region. White settlement was strongly discouraged. However, at the close of the American Revolution the British ceded control of the region to the Americans (although they took their sweet time getting out of town) and European settlers lost no time spilling over the Appalachians and on into the new territories.

In 1787 Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 that formally opened the region to settlement (and not coincidentally established the concept of public land sales as a way for the cash starved federal government to generate some revenue). Very quickly Lake Erie and it’s major tributaries became critical territory and conflicts frequently flared up as American, British and Indian interests intersected and collided in what was effectively the new American frontier. For thousands of years the Native Americans had used the Maumee River as a major trade route. The European powers and the new American republic recognized the river as the western gateway to the rich lands of the Ohio Country interior (today’s western Ohio, Indiana and lower Michigan). All sides considered control of the waterway a strategic necessity.

The Maumee River basin drains regions of three states

After the close of the American Revolution the British never really vacated the region. They maintained a number of outposts in places such as Detroit (yes, that Detroit) and Fort Miami near the city of Maumee, conducted a regular business of illegal trade with the local Indians and did a lucrative side business in fomenting anti-American sentiment among the tribes of the Western Confederacy.

Sadly, today all that’s left of Fort Miami are some low triangular mounds that trace the outline of the stockade

This all erupted into the Northwest Indian War, culminating in 1794 with the Battle of Fallen Timbers just a few miles away from Fort Miami. The American general, ‘Mad’ Anthony Wayne decisively defeated the tribes of the Western Confederacy on a piece of terrain marked by a tangle of trees that had been blown down during a violent storm. The Indians retreated towards what they thought would be refuge with the British garrison at Fort Miami, but the British commander refused to open the stockade. The surviving Indians scattered and the war was over. Not long after the British abandoned the fort and marched north into Canada.

Nineteen years later the British are back. It’s 1813 and the War of 1812 is raging. The Lake Erie basin is a critical theater of operations. The Americans have decided to invade lower Canada and move to establish a fort and supply depot on the Maumee River to support the invasion. The commander, General William Henry Harrison, selects a spot on a bluff on the south side of the river that overlooks the first set of rapids. These rapids serve as a natural choke point for any boats, barges, canoes or naval vessels trying to move upstream from Lake Erie. It is an ideally situated fort, and whoever controls it also controls all movement on the river. The British want it, and want it bad.

The fort was named Fort Meigs after Ohio governor Return J. Meigs. The fort was originally garrisoned with a few Regular Army troops and Ohio militia. Construction started in February 1813 and just two months later the fort was placed under siege by British forces that had marched down out of Canada and re-occupied the old Fort Miami stockade. Forts Meigs and Miami were located a mere two miles from each other, on opposite sides of the river.

Fort Meigs has been rebuilt and is now an active historical museum site

The siege was broken when 1,200 Kentucky militia moved up from Cincinnati and followed the Maumee River to the fort. In May of 1813 a series of short, sharp ground skirmishes resulted in the defeat of the British and their Indian allies, and the British abandoned Fort Miami. It’s this first siege, and the Kentucky militia’s involvement, that bring us to the real point of this post. (Took me a while to get here, didn’t it?)

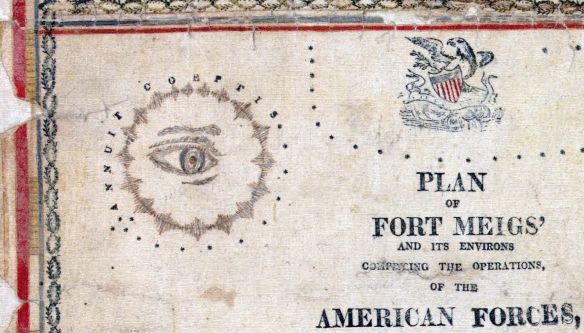

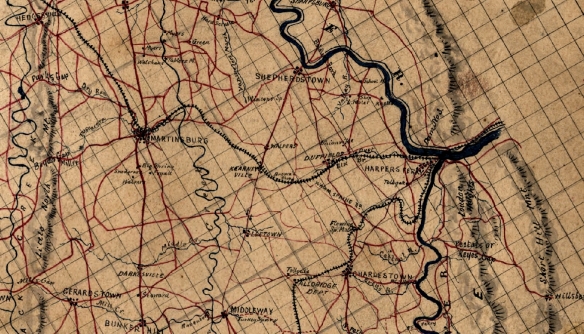

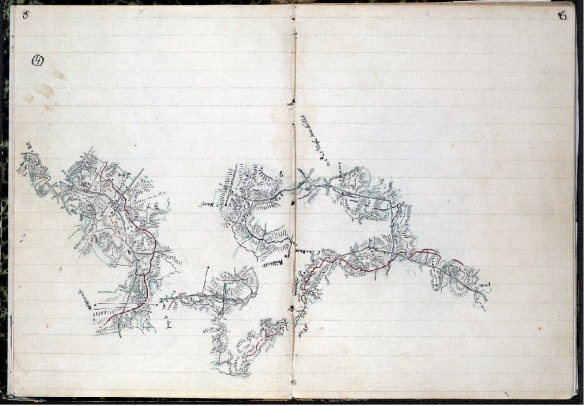

Part of the record of the siege is a vividly detailed battle map drawn up by an officer of the Kentucky Militia, Captain William Sebree. Seabree was the commander of a company of infantry that drew most members from around Campbell County, Kentucky. The company was designated the 8th Company of the 10th Regiment, Kentucky Light Infantry that was commanded by Lt. Col. William Boswell. Indications are that Sebree compiled his map after returning to Kentucky at the end of the war. However, the amount of detail in the map – both the cartographic representation of natural and man made features and the written depictions of the flow of the skirmishes and battles – makes it clear that Captain Sebree was working from a rich collection of original material. Certainly he kept a detailed journal while in command and also had copies of his company’s daily logs and reports. He likely also had access to the regimental papers and solicited input from other unit commanders and common soldiers. What emerged was less an authoritative battle map and more a piece of patriotic folk art that still manages to convey in some detail the ebb and flow of battle.

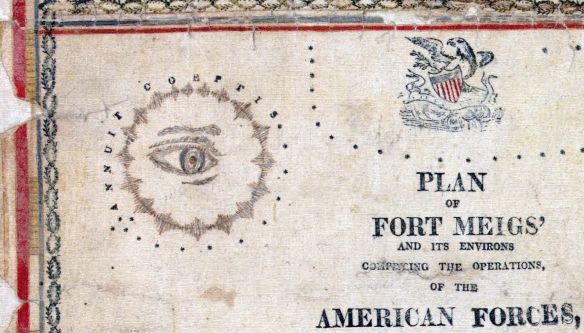

Captain William Sebree’s ‘Plan of Fort Meigs’ and It’s Environs’ (click to enlarge)

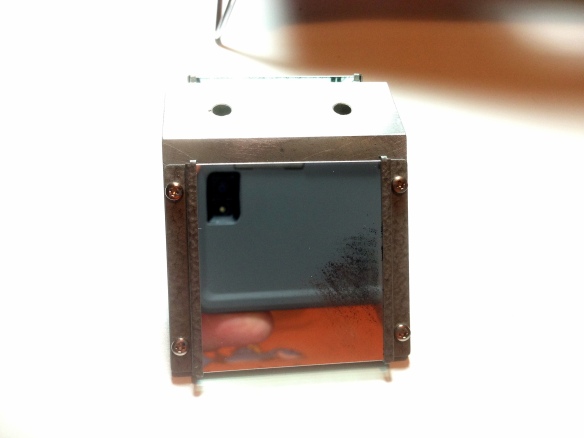

The map shows that Sebree had an eye for hard military detail, such as the detailed depiction of the Fort Meigs stockade area:

(Click to enlarge)

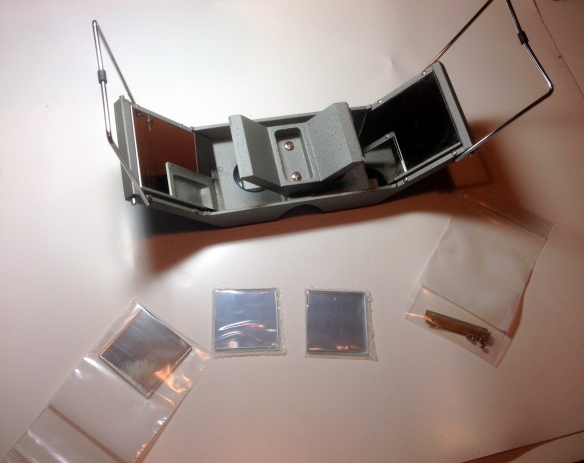

Or the details of the British artillery positions just across the river from the fort:

(Click to enlarge)

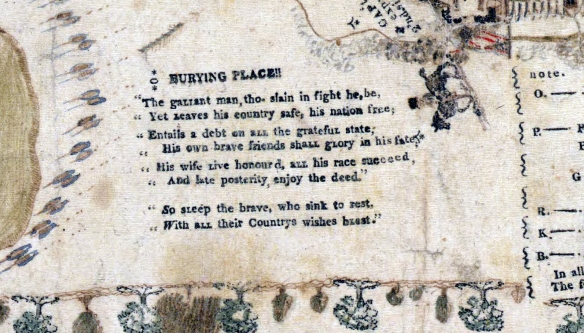

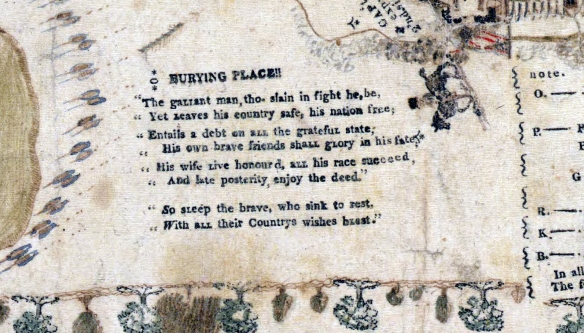

But he couldn’t resist a bit of patriotic sentimentality:

(Click to enlarge)

And a good bit of artistic embellishment – mounted Indians, boats on the river, trees bending in the breeze, and dogs (dogs?):

(Click to enlarge)

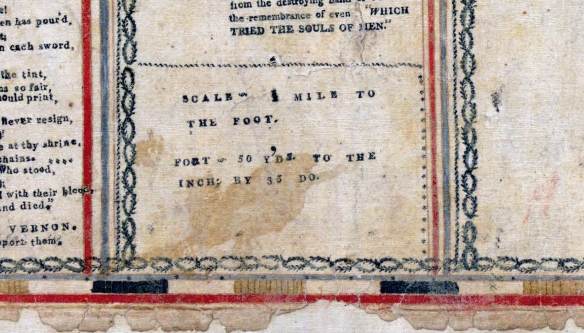

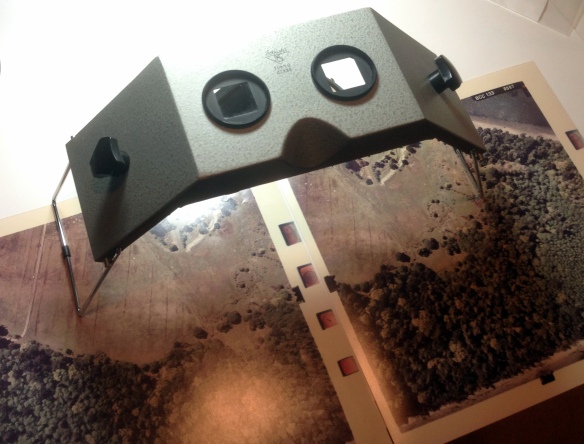

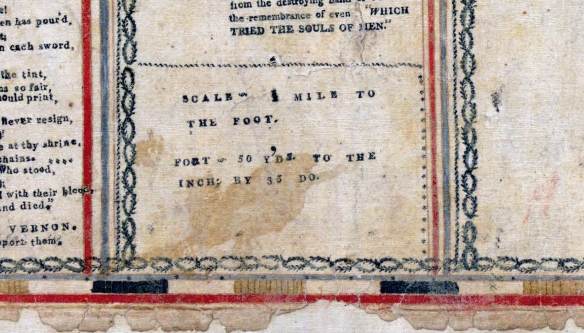

It’s clear Captain Sebree was not a trained topographer. Many topographic details are badly out of proportion and he makes use of different scales:

There is no north arrow or compass rose (on this map, north is to the right). But there is perhaps the more important (to Sebree) ‘all seeing eye’ with the phrase annuit coeptis (Providence favors this endeavor). This symbol is taken from the Great Seal of the United States, adopted around 1782, and was in common use in the early 19th century. However, it may also indicate that Captain Sebree was a Mason, and the first authorized Masonic Lodge in northwestern Ohio was organized by the American officers stationed at Fort Meigs in 1813. It is highly likely that Captain Sebree was a Mason (as were many officers of his time) and a member of this lodge. This is all speculation on my part, but I think the threads are there.

The map appears to be a commercial product. It’s a mix of set type and what looks to be woodcut printing. My guess is that Captain Sebree had these printed for commercial sale to a public eager for a memento of America’s glorious victory over the British and their Indian allies, or he sold copies by subscription. However, I know of only one existing copy that is in the Library of Congress map collection.

It seems Captain Sebree was an adventurous fellow. He was born in Virginia in 1776, migrated to Kentucky and settled in Boone County, studied law after the war and eventually moved to Pensacola, Florida where he was appointed the federal marshall for the territory of West Florida. He died in 1827 of yellow fever and is buried in Saint Michael’s Cemetery in Pensacola.

Dan Wilkins runs a great blog about the War of 1812 and has a section devoted to Fort Meigs and the events that took place there. I lived in Maumee for almost 10 years and have a deep interest in the history of the fort and the battles that took place around it. But until I read Dan’s blog I had no idea that remnants of the original British canon pits dug during the first siege were still visible in the old Fort Meigs Cemetery just east of the fort. If you have any interest in the War of 1812, and in particular the events that took place in the Northwest Territory, I recommend you spend some time taking a look at Dan’s writings.

– Brian