Progress is good.

Without progress we wouldn’t have a lot of great things like:

Penicillin

Computers

Electronic ignition

Cell phones

Frozen pizza

Few could argue that these developments have significantly enriched our lives or made them easier. (Have an issue with electronic ignition being on the list? Ever hand crank a car to get it started?)

But too many people equate change with progress. If you change something, particularly if you change something that few people really understand, you can claim progress and nobody really stops to say, “Uh, I don’t think so”.

So it is today with my ‘profession’ – Geospatial Information Services (GIS).

I put the term profession in quotes when using it in conjunction with GIS, because I’m not really sure GIS is a profession. It certainly is a job – there are thousands of people working GIS jobs around the world, but in my opinion it’s not really a profession, not yet anyway.

And the story of GIS is the story of change without real progress.

Background. I have been working in the mapping, survey and geographic analysis field almost continuously since 1980. I watched as the US military, particularly the Army geospatial engineering field, transitioned from the old manual analysis and production methods to computer-based analysis and production. When I started it was all hand drawn overlays and paper maps. Today it is GIS software and web-based mapping services. I have certainly seen change in my field – fundamental, earth shaking change. I’m not so sure I’ve really seen a lot of progress. In fact, I would claim we’ve actually moved backwards in our ability to provide clear analysis and decision support tools to our customers. We have moved forward with change, yet backwards with progress.

How can that be? Simple. The GIS field has traded fundamental skills for computer application expertise, and the lack of fundamental skills and the ability to do critical analysis makes the field a slave to the software.

Change without progress.

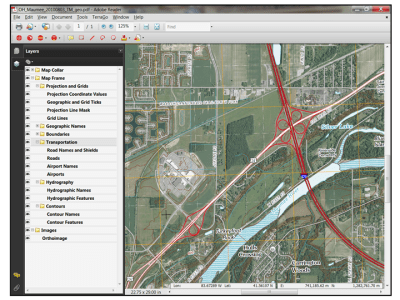

Go up to any GIS professional and ask him or her to describe their job. They will stumble around trying to explain it to you and invariably the words ‘arcgis’, ‘computer’, ‘database’ and ‘web maps’ will leak out. The GIS professionals today can not think about, describe or relate their jobs without first thinking about the computer application. For far too many of them the computer application is their job. Continue the line of questioning and ask them if they think they can continue to do their job effectively without their computers and GIS software, even for just a short period of time. Again, most will say no – in their minds their ‘profession’ is inseparable from and defined by the software.

Ask a civil engineer to define his or her profession. You won’t hear words like ‘autocad’ or ‘microstation’ slip out, yet AutoCAD and MicroStation are the two leading engineering design packages in use around the world. Reason? Civil engineers don’t define their profession in relation to software applications. Civil engineers are educated and trained to solve complex issues using analytical skills. I work every day with extremely competent civil engineers who plan and manage multi-million dollar projects, yet they don’t even know how to open up an AutoCAD drawing file on their desktop computer. They were hired for their engineering and problem solving expertise. Software applications are merely enabling technologies that allow them to work more efficiently.

Put the same question to a land surveyor. You won’t hear terms like ‘terramodel’, ‘geomatics office’, or ‘civil3d’. These are software packages that enable surveyors to do their jobs more effectively and efficiently, but they do not define the profession. The survey profession is defined by a set of standards tied to analytical and problem solving skills.

In each of these cases the profession defined what it needed from the software and the vendors responded. In the GIS field things evolved the other way. In the beginning (way back in the 1970s), the term ‘GIS’ defined software, not a skill set (the original term GIS stood for ‘geographic information software’ and has only recently morphed into ‘geospatial information system’). Other professions like Forestry, Geology and Geography started using GIS technology to better manage large amounts of data that had a spatial component – things like timber stands, mineral lease boundaries and census data. The software was revolutionary, but it was an enabling technology and not an end in itself. Because the software was used by a broad range of professions there was little standardization.

As the years progressed and GIS software matured, more and more individuals became captivated by the GIS concept. I will admit, in addition to having powerful analytical capabilities GIS packages like ESRI’s ArcGIS are just plain fun to work with. However, these applications do little to enforce standards. Everybody gets to do what they want. That’s not the software’s fault – it’s up to the GIS professional to apply recognized standards. But before you can have standards you have to clearly define your profession, and if you can’t define your profession how can you define your standards? It was as though GIS had no conceptual roots – a discipline born anew, without heritage or precedent. And nobody wanted to take ownership. So, heavy GIS software user self identified themselves as ‘professionals’ and happily motored along, defining themselves any way they wanted. As a result the GIS profession has become a primordal soup of software users with varying skill sets. Some are damned sharp, other’s have trouble finding the ArcGIS icon on their computer desktop. Yet all get to claim the title of ‘GIS Professional’ because, well, nobody told ’em they can’t.*

I refuse to be defined by a software package. I am better than that, and my employers didn’t hire me for my button pushing skills. They hired me to solve complex problems and provide unique services no other group in the organization could provide. If I can provide the answer by scribbling a few calculations on a notepad, great. If I have to fire up high end GIS software to run a complex analysis, OK. How I arrive at the solution is immaterial to my employer, they just want an accurate answer that conforms to the established standards of the disciplines I’m touching.

But if GIS is the software, what is the discipline? What melds geography, geology, forestry, hydrology, landform analysis, civil and structural engineering, environmental science and surveying into a multi-discipline approach to problem solving? What discipline applies the best approach to describing the land and the structures on it and features below it with accuracy and precision? What discipline relates data using a multi-disciplinary approach to solve the unique and complex problems beyond the realm of other earth science and engineering disciplines? That discipline doesn’t exist, you say?

Balderdash!

The discipline I describe has existed for over 150 years. This discipline opened the American west to exploration and settlement, unlocked the vast natural resources of this country and helped fuel it’s rise to an economic world power, it charted America’s home waters for safe navigation, mapped vast expanses of Central and South America and even mapped the Moon to identify safe landing areas for our Apollo missions. Most came to this discipline from other professions. It drew in its share of civil engineers, geologists, surveyors and geographers. It was once the leading career choice for the top graduates from West Point. This discipline started to die out in the 1980s, with the rise of specialization and computerization, when we tried to replace broad experience with computer algorithms. Yet it is a discipline that is still as relevant today as it was in the mid-1800s, perhaps even more so as our infrastructure, development, enviromental, and energy issues start to intersect in ways only spatially-based analysis can address.

This is the discipline of the old Topographer!

|

A topographer of the old Coast & Geodetic Survey, conducting

what is essentially a geospatial analysis using a plane table survey set |

By definition, a topographer is someone who precisely maps and describes a portion of the earth’s surface and the man made features on it. That is about as elegant a description of what I do as any I’ve found.

So, don’t call me a GIS professional, analyst, manager, coordinator or anything else related to a software application.

Call me a Topographer!

– Brian

* I understand we have this thing called the GISP certification program. In its current form it’s a joke. What does it certify? Other professions with established licensing standards, like the engineering and survey fields laugh at the GISP certification program. How can you certify against something that doesn’t have standards?