Well kiddies, I’m back from San Diego and the 2014 ESRI International User Conference. This is my third conference in five years, and it’s starting to feel like Groundhog Day.

Now please, do not get me wrong – it was a very good conference and in some respects it was a great conference. I and my team learned a lot and picked up a lot of new information. But in the plenary and in the technical sessions and presentations side it was the same drumbeat we’ve been hearing for the past several years – ‘rich’ web maps and apps (could someone in ESRI please tell me just what ‘rich’ means?), ArcGIS as an integrated system, not just a bunch of parts, ArcGIS Online, ArcGIS Online, ArcGIS Online, yaddah, yaddah, yaddah. In the Solutions Expo (i.e., vendor displays) it was the same vendors, many in the same locations, showing the same stuff, giving the same spiel, etc.

You know, Groundhog Day. C’mon ESRI, mix it up a bit. It’s getting a little stale.

OK, that’s out of the way. Let’s change tack. If you listened closely to the presentations and have been paying attention to what ESRI’s been doing in the past few months you were able to tease out some great information regarding new and emerging capabilities. Let’s start with one of ESRI’s current flagship product, ArcGIS Online.

If anyone reading this blog still doubts that ESRI considers ArcGIS Online and web mapping a central part of ESRI’s GIS universe then this UC would have set you straight. The message was obvious and unmistakable, like a croquet mallet to the head. ArcGIS Online is here to stay, is only going to get bigger, and if you are going to play in the ESRI sandbox you need to know (and buy into) ArcGIS Online. I didn’t attend a single ESRI session, whether it was the plenary or a one-on-one discussion with a product expert where the topic of ArcGIS Online integration didn’t pop up early and often. Most vendors I talked to – and certainly all of those that ‘got it’ – had ArcGIS Online integration as a key selling point for their product or service. Heck, even IBM with their painfully complex work order management program called Maximo ‘got it’ and touted how I could now ‘easily and seamlessly’ integrate ArcGIS Online feature services with Maximo. Anybody who knows Maximo knows it doesn’t do anything ‘easily and seamlessly’. I don’t really think Maximo can use hosted feature services from ArcGIS Online, at least not yet. The REST endpoints I saw Maximo consuming looked like dynamic map services. But at least the IBM sales team took the time to read the memo from Redlands.

The ArcGIS Online product space was the single biggest product presence ESRI had set up in the Expo. It was huge, and a reflection of the importance ESRI places on the product

ESRI’s incessant chatter about ArcGIS Online would have fallen flat with those who are long time users of the product if ESRI had not done a product update just a few weeks ago. The July update of ArcGIS Online included a number of significant improvements and new features that signaled to those who know the product that ESRI is serious about ArcGIS Online being more than just a toy for making simple web maps. The upgrades in system security certification, administration tools, data management, data integration, analysis and cartographic tools shows ESRI has full confidence in ArcGIS Online as a serious enterprise tool. I’ll admit that a few years ago I was having doubts that ESRI would be able to pull this off. Today I’m convinced that ArcGIS Online and web mapping is the most significant development in geographic content delivery since the invention of the printing press.

This year I spent more time wandering the Solutions Expo hall than I did attending the technical sessions. In past years there were sessions I felt I just couldn’t miss, but this year my technical needs were somewhat less well defined and I wanted to spend more time speaking with the vendors and visiting the ESRI product islands. It was time well spent.

One of the focuses (foci?) of this year’s plenary presentation was the issue of ‘open data’. Open data is nothing more than data that is available free to any user. Open data can take any format (though it is understood that for data to be truly ‘open’ it needs to be available in a non-proprietary format). For decades the federal and state governments have made GIS data available in a variety of GIS formats. A good example of this is census data. The data for most censuses held in the last 40 years or so is freely available in GIS format from the US government. It’s easy to pull that data into a GIS system and do all kinds of analysis against it. In fact, census data is one of the first data types that new GIS students learn to analyze in their core classes. In the same vein, many states make state-specific GIS data available from freely accessible data servers. Things like elevation data, transportation network data, hydrology, landcover and more have been commonly available for years.

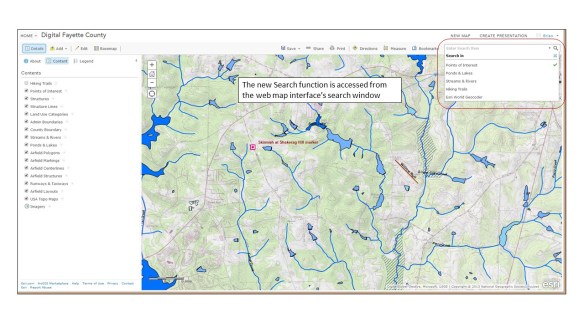

However, it was often difficult for smaller government entities – cities, counties, or regional authorities – to share out their public data because of the IT and GIS management overhead involved. Let’s face it, nobody makes money sharing out free data so there’s little incentive to put a lot of resources behind the effort. As a result a lot of currently available open GIS data is pretty stale. ESRI is backing a push to pump new vitality into the sharing of open data via the new Open Data tools embedded in ArcGIS Online (see, there it is again). OK, I admit that ArcGIS Online isn’t exactly free to the organization looking to share out data, but if you do happen to be an ArcGIS Online subscriber then setting up an Open Data site is fast and easy. One of the great concepts behind ESRI’s effort is that the organization is really sharing a feature service from which an Open Data user can extract the data. This means that the data should not suffer from ‘shelf life’ issues; as long as the data behind the feature service is regularly updated the Open Data user will have the latest and greatest representation of what’s being shared.

On one of my laps around the Expo floor I stopped at the Open Data demonstration kisoks set up in the ArcGIS Online area and talked through the concept and implementation with one of the ESRI technical reps. At first I didn’t think my organization would have much use for this feature, but after thinking about they types of data we routinely pass out to anyone that asks – road centerlines, jurisdictional boundaries, parcels, etc. – I began to think this might be of some value to us. In about 15 minutes she helped me set up my organization’s Open Data site and share some common use data out to the public. If for no other purpose, an Open Data site could lift some of the data distribution burden off of us.

The new Open Data tab in ArcGIS Online allows the administrator to configure an open data page from which the organization can share data with the public

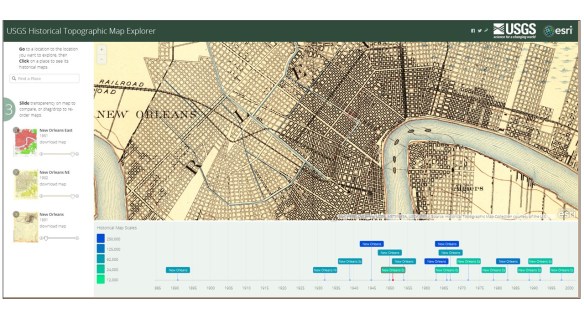

Another lap took me to the US Geological Survey information tables. The USGS table was set up in the Federal Government area and while most of the agencies suffered from a serious lack of attendee interest (and I pity the poor souls who had to man the Veteran’s Administration table), the USGS tables were doing a good business. The USGS reps were stirring the pot a bit. It seems that there’s a move afoot in the USGS to do away with the National Atlas. I’m not sure yet how I feel about this move. Clearly elimination of the National Atlas is a cost cutting move (and the USGS makes no bones about it on their website), but if the same digital data can be made available via other portals, like the National Map portal, then this may all be a moot point. Still, this is the National Atlas and as such should be a point of pride not just for the USGS but for the nation. If for no other reason than that I’d keep it alive. The USGS reps working the tables were clearly pro-National Atlas and were running a petition campaign to garner support to keep the program going.

I also spent some time discussing the new US Topo series of maps with the USGS reps. If you’ve read any of my posts on the US Topo maps you know that from a cartographic perspective I think they stink. The map base – imagery – is poorly selected and processed and the maps looks like crap when printed out. That’s the basic problem; the US Topo series are compiled as though the intent is to print them out full scale for use in the field. They carry full legends and marginal data. However, it’s clear they were compiled specifically to look best on a back-lit computer screen. When printed out the maps are dark, muddy and the image data is difficult to discern. When I brought this up to one of the USGS reps she turned her badge around to indicate she was speaking for herself and said, “I agree completely, and we get a lot of complaints about the visual and cartographic quality of these maps.” Here’s hoping the USGS doesn’t go tone-deaf on this issue and takes steps to improve the quality of the US Topo series. She also let me know that there’s growing support within the USGS to provide the US Topo series maps not just in GeoPDF format but also in GeoTIFF. This would be a great move, especially if the USGS provided them in a collarless format for use in systems like ArcGIS for Desktop.

I took the time to mosey over to the Trimble display area and talk to a rep about my favorite Trimble issue – the lack of a Google certified version of Android on their very capable (and very expensive) Juno 5-series of handheld data collectors. I’ve bugged Trimble so much about this that I have to assume my picture is hanging on a dartboard in the executive conference room at Trimble’s headquarters. I got the same response out of the Trimble rep that I’ve been getting for about a year now, “We hear it’s coming but we don’t know when”. Yeah right.

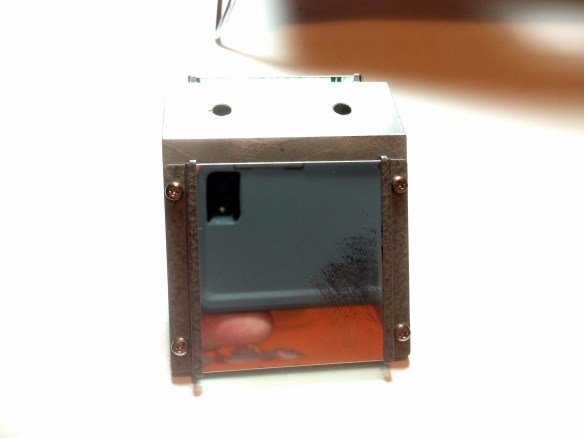

After I left the Trimble area I found myself a few rows over at the table of a company I’d never heard of before, Cedar Tree Technologies. It was just a couple of guys with a couple of pieces of hardware, but my eye caught something that looked a lot like a beefed up smartphone and the guys at the booth were eager to give me their story. It seems that Cedar Tree Technologies is a brand new spin-off of Juniper Systems, a company that’s been making rugged handheld systems for the surveying and GIS community since the 1990’s. Cedar Tree’s specific focus is on the Android OS, and each of the devices on display were running Google certified versions of Android 4.2. The device that caught my eye was the CT4. The CT4 is what it looked like – a ruggedized smartphone that runs on Android. It looked like an OK product with very good specs – a quad core processor running at 1.2 GHz, a 4.3″ Gorilla Glass display, and 8 mp camera, a 3000 mAh battery, Bluetooth and an IP68 rating. It did have a few drawbacks – only 16 gig of system memory and a 3G (not 4G or LTE) cell radio, and I forgot to ask if it was fully GNSS capable. But here’s the kicker – this damned thing is only $489! Roughly one third the price of the baseline Juno 5, yet it looks like it offers 3/4 or more more of the Juno’s capability. You can bet I’ll be contacting Cedar Tree about borrowing one of these for an evaluation.

He’s smiling because he thinks he’s got Trimble beat in the Android space. I think he might be right!

The Cedar Tree Technologies CT4. Perhaps the first truly usable Android-based field data collector

OK, I don’t want to get too far into the weeds on other topics of interest, so let me just do some quick summaries:

- I talked to Trimble, Leica, Carlson, Juniper and Topcon reps about their software offerings. All plan to remain tightly wedded to the Windows Mobile 6.5 OS (a.k.a., Windows Embedded Handheld), which hasn’t had any significant updates for over 2 years. Many of the reps indicated that the mobile version of Windows 8 still has some issues and they are very reluctant to move in that direction. So it looks like the industry will be stuck with an archaic and moribund OS for some time yet

- What the world needs, in addition to a good 5¢ cigar, is a good spatially based document management system. Lord knows my organization is in desperate need of something like this. I saw only one document management system vendor at the show, and their system has a strong dependency on ArcGIS Online (there it is again). I think this is a market area that is ripe for exploitation. The tools are now in place with ArcGIS Online and reliable cloud services to bring this type of functionality quickly and cheaply to an enterprise and I’d love to see some new developments in this area. Pleeeeze!

- I attended a very interesting working session where the GIS team from Pierce County, WA discussed their adoption of enterprise GIS and ArcGIS Online. I felt like I was sitting through a presentation I had written about my own team’s struggles and experiences. Like us, Pierce County faced a lot of push-back and foot dragging from their IT department on implementing IT-dependent GIS initiatives, and productivity among the county’s field maintenance crews suffered. Here’s my point – for every GIS/IT success story I’ve heard or read about I’ve heard an equal number of stories where thick-headed IT departments get in the way of a successful GIS initiative. If you are IT and don’t fully support the GIS initiatives in your organization then watch out. You will wake up one day soon to find you’ve been replaced by a cloud based service. It’s happened in my organization and it’s happening across the industry.

- How come I never heard of the Association of American Geographers? I’m not joking. I’ve been in this industry for over 30 years and have been attending trade shows for all of that time. I’ve heard of the ASPRS, the American Society of Photogrammetry and others, but never the Association of American Geographers. Seems like a good organization. May have to join!

- Like a good 5¢ cigar, the world also needs more quality geospatial sciences masters program options. I talked to a number of the universities set up at the conference and while they all seemed to be offering quality programs, too many of them are targeted at the professional student, someone who heads into a masters program directly from a bachelors program. For example, here in Atlanta the Georgia State University offers what looks like a cracking good geosciences masters program with a focus on geospatial science, but it’s structured so that all of the coursework is classroom focused and only offered during working hours. For someone making a living in the real world this type of program really isn’t feasible. We need more fully on-line options and more local colleges and universities to offer evening and weekend programs.

- Let’s get back on the ArcGIS Online horse and discuss a very interesting service that the developers tell me is under serious consideration. One of the gripes that users of Collector for ArcGIS have is the lousy positions that are provided by the GPS/GNSS receivers on handheld units. Keep in mind that this is not a Collector issue, but a hardware issue. One of the improvements ESRI is looking at is a subscription based correction service for use with Collector. It will probably work like this – collect a point or a series of verticies and when they are synced with the ArcGIS Online server the points first pass through a correction service before being passed on to ArcGIS Online. This will likely be a single base station correction solution, but it could offer sub-meter accuracy if using a data collector with a more advanced GPS/GNSS receiver (sorry, this will not work with your iPhone or Android smartphone because of the low quality receivers they use). Sort of like on-the-fly post processing. A very interesting concept, and it could move a lot of hardware manufacturers like Trimble, Topcon and Leica to put out low(er) cost Android-based field data collectors with improved receivers

Before I go, some kudos:

- To the City of San Diego. I can’t think of a better place to hold this conference

- To GIS, Inc for a wonderful dinner cruise with NO sales pressure (Mrs. OldTopographer just loved it!)

- To Andrew Stauffer from ESRI and fellow BGSU grad. Andrew provided invaluable support to our organization over the past few years while we worked through our ArcGIS Online implementation issues. I finally got to meet him in person and thank him

- To Pat Wallis from ESRI who proved you can hold down a serious job and still be a 1990’s era ‘dude’

- To Courtney Claessens and Lauri Dafner from ESRI who entertained all of my dumb questions about Open Data

- To Kurt Schowppe from ESRI. I’m sure my pool party invite got lost in the mail <grin>

- To Adam Carnow, for putting up with all of my other dumb questions and requests

- To all the great people I bumped into at random and had wonderful conversations with

And finally, it was good to see my alma mater making a showing at the Map Gallery exhibition. Go Falcons!

– Brian