In the Geospatial Engineering world there is one Big Dog software developer and a pack of miniature chihuahuas snapping at its heels. The Big Dog is ESRI, developers of the ArcGIS suite of software products.

ESRI dominates the GIS (geospatial information systems) software field in the same way Microsoft dominates the computer operating system field – there are competitors but nobody even comes close to the market share that ESRI developed and has held for decades.

But unlike Microsoft, ESRI didn’t get to where it is by being predatory and imposing crushing licensing agreements on its clients. ESRI got it’s market share the old fashioned way – by simply being the best product in the market for the target consumer group. ArcGIS is the software product that moved the traditional discipline of topography out of the paper map and overlay era and into the computer-based, analysis driven discipline of Geospatial Engineering.

ESRI was started by Jack Dangermond, someone I refer to as a “Birkenstock wearin’, Volvo drivin’, granola crunchin’ hippie.” In the late 1960s and early 70s, building on pioneer work that had been done on early GIS concepts and development in Canada (where the discipline of GIS got its start), Dangermond created a land cover analysis program called ArcInfo and released it as a commercial product in the early 1980s.

Early versions of ArcInfo were hindered by limited computer processing, storage and graphics capability. Geospatial analysis is very much a visual discipline – you’re making maps, after all. Early desktop hardware simply didn’t have the capability and capacity to bring the full visual mapping experience to the user. Up through the mid 1990s only expensive Unix workstations could handle that level of processing. This all changed around 1995 when desktop computing power started increasing exponentially with each new processor design while at the same time hardware prices dropped like a brick. Almost overnight inexpensive desktop computers appeared that could easily handle the processing and graphics demands a software package like ArcInfo placed on them. I was working as a GIS program manager for the US Army when this hardware revolution hit the field and watched as in less than two years inexpensive desktop PCs caught up with and then quickly surpassed the processing power of the Unix-based Sun, Silicon Graphics and HP systems we had been relying on. What also helped was Microsoft’s release of WindowsNT at about the same time. Finally we had a serious network-ready enterprise operating system running on high capacity hardware that didn’t make our budget guys weep every time we said we needed to do an upgrade.

ArcInfo is the flagship product of the ESRI line and is extremely powerful software. But in the 1980s ESRI realized that not everyone needed the processing power of ArcInfo (nor could they afford the nausea-inducing cost of an ArcInfo software license). ESRI introduced a lightweight version of ArcInfo that included most of the visualization capability of the high end package but left out the heavyweight analysis and data development functionality. They named it ArcView. It was priced right – something small organizations and even individuals serious about GIS could afford (if I remember correctly the GSA schedule price for a single ArcView license ran around $600 in 2000). The vast majority of today’s GIS professionals cut their teeth on ArcView.

But ESRI’s real contribution to the GIS profession is the development of data types that both support complex spatial analysis and can be shared across different software platforms. It is Dangermond’s vision that GIS-based mapping and analysis solutions should not be a stovepipe, but a shared resource. This drove ESRI to develop the concept of the geodatabase. A geodatabase is a collection of data in a standard relational database management system (RDBMS) like Oracle or SQL Server, but the data has very unique spatial values (location in x, y and z coordinates) assigned to it. This means that GIS software can leverage the spatial values to relate the data in a location context and other RDBMS-based software systems can easily share their information with the geodatabase. The geodatabase only needs to store GIS-unique features and can pull and do analysis against associated data in another database.

ESRI also developed a version of the geodatabase that does not require a high powered relational database management system as it’s foundation. About a decade ago ESRI introduced the concept of a file-based geodatabase designed for use by small organizations or groups. The file geodatabase is a simple to create yet powerful and extremely flexible data format that brings most of the power of the relational database and complex data analysis to the desktop machine and the individual user.

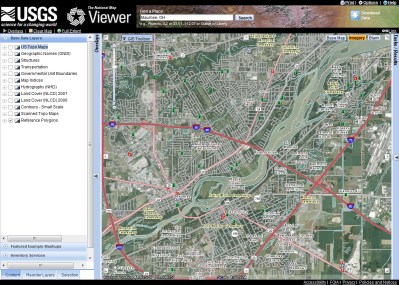

But what does the future hold? ESRI realized long ago that the Internet was the map content delivery vehicle of the future. Paper maps were headed to obsolescence and what Jack Dangermond describes as the ‘rich web map’ would quickly become the geospatial data visualization and analysis tool of the future. He’s right, but only very recently has web technology started to catch up with his vision.

For the better part of a decade it was possible to hire professional web developers to create some very nice web mapping applications built on ESRIs early web technology called ArcIMS. The problem was that those applications were difficult to develop, difficult to maintain, and required a lot of heavy weight back-end web and database server technology. Only large enterprises and governments could support the hardware, software, development and maintenance costs. ESRI’s web solutions were very much limited by the immature web development technologies available at the time. It is ESRI’s vision that even the average geospatial professional working for a small business or local government should be able to develop, launch and maintain high quality web maps that bring value to the organization they support. ESRI started laying the groundwork for this vision back with their ArcGIS 9 series of software releases and the development of things like ArcGIS Server and the concept of Map Services. Two years ago they released ArcGIS 10 that brought a lot of maturity to the concept of integrated and streamlined web mapping using the Microsoft Silverlight and Adobe Flex web development environments, and the launch of ArcGIS Online with its peek into the future concept of ‘cloud services’ for hosting GIS data, services and web maps.

At it’s recent worldwide user’s conference ESRI announced the pending release of ArcGIS 10.1 with better integrated and streamlined web development tools. But ESRI also announced two new developments that are generating a lot of interest. The first is the announcement that ESRI has partnered with Amazon.com to host robust, enterprise-level cloud services for GIS web mapping, data hosting and application development. The idea is that an enterprise purchases an ArcGIS Server software license, passes that license over to Amazon and Amazon stands up and maintains the necessary database and web development environment for the enterprise. This is a huge development because it can free the GIS group supporting the enterprise from the often onerous and restrictive shackles placed on it by their local IT department.

The other announcement was the pending release of the ArcGIS Online Organizational Account program. The Organizational Account program appears to be targeted as smaller enterprises and groups that don’t have the money or need to purchase full-up cloud services like those offered by Amazon. Under the Organizational Account concept an organization will be able to purchase data and web hosting services from ESRI on a subscription basis. It is still a ‘cloud’ model, but on a smaller, more tailorable scale that should allow small organizations to enjoy most of the capabilities of a full-up ArcGIS Server implementation.

The last good thing I need to discuss is another little-known program released this year – the concept of ArcGIS for home or personal use. ESRI’s software licensing fees have escalated to the point that the geospatial professional simply can’t afford a copy to use to keep his or her skills sharp. I noted above that the GSA price for an ArcView license used to run about $600 – a bearable cost if you were serious about GIS. However, the cost for an ArcView license now hovers around $1,600, far too much for even the serious home user. This year ESRI announced the ArcGIS for Home Use program. Anyone can purchase a 1-year license of ArcView for $100, a very reasonable price. Not only does this $100 include on-line software training and support, but you also get a very extensive suite of add-on modules like 3D Analyst, Spatial Analyst and Geostatistical Analyst. The total value of the software you get for your $100 subscription comes to over $10,000. One hell of a deal. Of course there are restrictions attached to this deal. The intent of the home use program is just that – you can only use it at home. You can also only use it for personal development/training purposes or non-profit use. Still, like I said, it’s one hell of a deal.

__________________________________________________________

Now, it’s not all rainbows and unicorns when it comes to ArcGIS and ESRI’s position in the GIS world. All this GIS goodness is of little use unless it’s leveraged in an environment with clearly defined professional standards. Nor can you allow a professional discipline to be defined by a software application or be inexorably joined to a piece of software. This is where ESRI’s has failed the geospatial community, and they have failed in ways they can’t even visualize from where they sit.

Here’s the reality: geospatial engineering is the discipline, the term geospatial information systems – GIS – merely describes the tools geospatial professionals use to do their job. Where ESRI has failed is in using its industry position and influence to help clearly delineate the difference between the two. As a result, far too many engineering professionals view geospatial professionals as little more than button pushing software monkeys, one step up from data entry clerks.

Part of the culture Jack Dangermond has fostered and progressed through ESRI is the idea that GIS is for everyone and nobody owns it. What he is effectively saying is that GIS is the discipline; the tools and the software drive the field, not the other way around.

While community ownership is a noble goal, ESRI’s dominance of the field gives lie to that very philosophy. Effectively, ESRI ‘owns’ GIS; it is by far the world’s largest GIS software developer. It has either developed or successfully implemented most of the recognized spatial analysis processes in use today. It’s data management features have driven the development of most of the spatial data standards in use today. The vast majority of geospatial professionals worldwide learned their trade using ArcGIS.

What is lacking, however, is a clear and recognized definition of just what a geospatial professional is. Dangermond is correct when he claims it’s not his role to define what a geospatial professional should be – that is the job of the geospatial field and industry as a whole. But Dangermond has been the biggest catalyst in the geospatial world for the last 30 years. He and the resources he commands through ESRI have been in the best position to cajole and coerce the private sector, academia and the government to establish the roles, practices and responsibilities that define Geospatial Engineering as a formal discipline. He should have been the single biggest champion of the concept of Geospatial Engineering as a professional discipline. Instead he’s been pretty much silent on the whole issue.

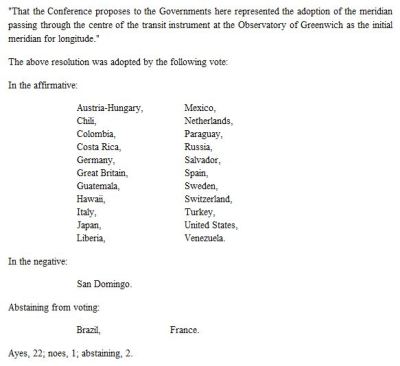

It is only in the last few years that the US Department of Labor developed a formal competency model for GIS (GIS, not Geospatial Engineering), and the GIS Professional Certification program is just starting to get its feet on the ground (after a disastrous grandfathering period that allowed perhaps hundreds of clearly unqualified individuals to get a GISP certificate and do damage to the reputation of the geospatial profession that may take years to overcome). Great, but all this should have happened 20 years ago.

What this means is that Geospatial Engineering is not respected as a professional discipline. I can tell you from long personal experience that geospatial professionals are looked down upon by other disciplines such as civil engineering and surveying, in large part because there are no testable and enforced standards that define us as a ‘profession’. Guess what – they are right!

_________________________________________________________

Many readers are probably asking themselves “Huh? What’s he getting at here?” I guess I’d ask the same question myself if I didn’t understand the background issues.

I’ve been a topographer and geospatial engineer for over 30 years. A few months back I laid out my initial arguments in a post titled In Praise of the Old Topographer. In that post I made the argument that Geospatial Engineering is just a logical continuation of the older and much respected profession of Topographer. I also outlined my argument that geospatial information systems, including ArcGIS, are merely the tools that the Geospatial Engineer uses to do his or her job.

With this post my goal was to identify one of the main culprits that is keeping Geospatial Engineering from fully maturing into a recognized profession, a profession with it’s own standards, roles and responsibilities.

ArcGIS is that culprit. On the one hand we have extraordinarily capable software that is almost single handedly responsible for bringing the discipline into the computer age and is poised to bring it fully into the age of world wide web. On the other hand, ArcGIS and it’s parent company ESRI are almost single handedly responsible for holding the discipline back and keeping it from taking it’s rightful place as a profession on par with other engineering disciplines.

For these reasons ArcGIS is the software I hate to love.